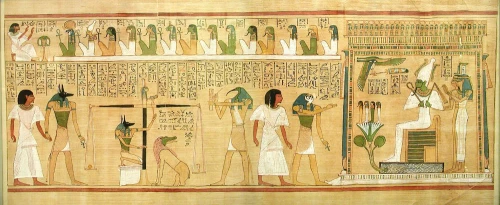

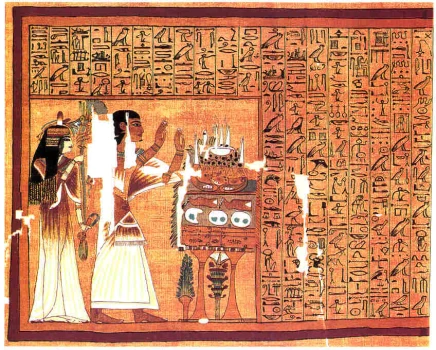

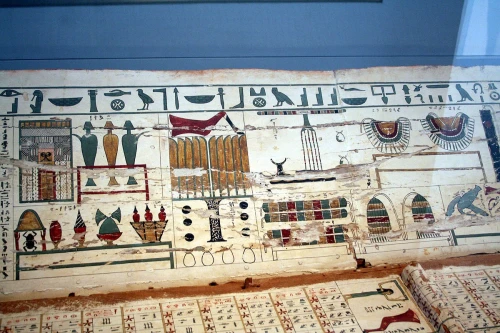

DECANS The Egyptians divided the night sky into 36 groups of stars, or decans, forming constellations. Each decan was named and associated with a corresponding god or goddess. For the Egyptians, the most impressive constellation in the sky was Orion, and the most important star was Sirius, called the Dog Star by the Greeks. Egyptian mythology equated Sirius with Isis and saw her as Orion’s companion. Together they dominated the southern sky. Sirius was the brightest star in the night sky, and when it appeared on the horizon around July 9, it was a sign that the Nile was about to rise and the season of inundation or flooding was about to begin. The inundation was crucial because the low Nile would mean less water for irrigation, causing a poor harvest. Every 10 days, a different decan appeared on the dawn horizon just before the sun rose. Thus the 36 decans could be used for measuring a 360-day year. By noting the positions of deans, the Egyptians also could tell time during the hours of the night. Pictures of the decans, or “star clocks,” were sometimes painted on coffin lids or tomb walls. Eventually “star clocks” were more of a decoration than a timekeeper, for, at the end of every year, they were about six hours behind time, and after several years, they were off by weeks. Although the decals and the god and goddesses who represented them were not used for telling time, they continued to appear on the walls and ceilings of tombs and as coffin decorations until the Greco-Roman period.

English

English

Spain

Spain