CHAMPOLLION, JEAN-FRANÇOIS

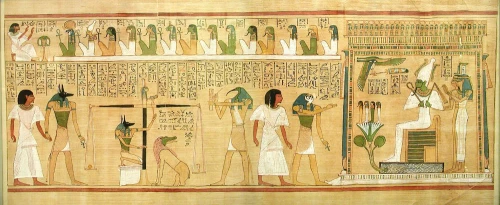

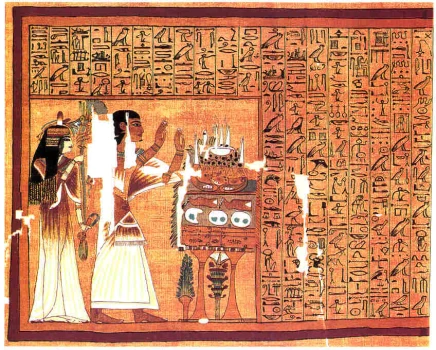

Little would be known about Egyptian mythology or religion today without the efforts of the great French linguist Jean-Francois Champollion. The ability to read hieroglyphs had been lost for 1,500 years before Champollion broke the code in 1822. As a youth, Champollion demonstrated an unusual ability to learn the language, and because his father was a librarian, he was surrounded by books written in many languages. He studied Latin, Greek, Arabic, Syriac, Chaldean, and Hebrew, but the language most helpful to him in translating hieroglyphs was Coptic, the language spoken in Egypt during the late period. Written in the Greek alphabet with seven special characters added, it is called Coptic because the Copts were the Egyptian Christians who used the script.

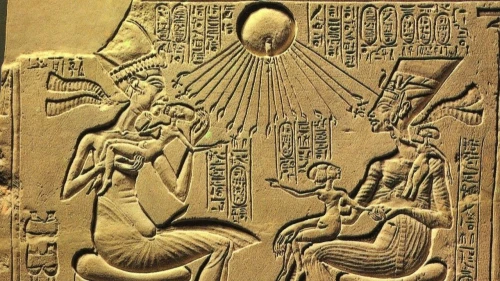

In 1808, when Champollion was still a teenager, he obtained a copy of the ROSETTA stone, and began his relentless pursuit of its meaning. From his earlier studies he knew there were three separate Egyptian scripts HIEROGLYPHIC picture writing; DEMOTIC, a later and more cursive form of writing; and HIERATIC, a cursive script used by priests. He deduced this by comparing hieratic papyri with hieroglyphic and demotic inscriptions. Champollion began to compare the hieroglyphic inscription of the Rosetta stone with its Greek counterpart. The key was the name PTOLEMY. It had long been known that the pharaohs wrote their names in ovals called CARTOUCHES. The oval represented a rope showing the pharaoh's dominion over all that the sun encircles. Since the Greek inscription mentioned the name Ptolemy, the name in a corresponding cartouche in the hieroglyphic text had to be Ptolemy. (Ptolmis was the Greco-Egyptian way of writing the name) With these letters established, Champollion went on to other names.

From an inscription on an obelisk found on the island of Philae, he had the name Cleopatra. (Champollion knew it was Cleopatra's name because the base of the obelisk had an inscription in Greek mentioning Cleopatra.) Champollion's work on the hieroglyphic alphabet is the basis of what we know today. The Egyptians omitted vowels but did have semi-vowels, sounds close to our vowels. And for most of their 3,000-year history, they did not have signs for the sounds L and O, which appear in Ptolemy's and Cleopatra's names.

Throughout his dedicated work on hieroglyphs, Champollion suffered from ill health, and it was with great difficulty that he traveled to Egypt to continue his studies. When he died in 1832 at the age of 41, a new group of scholars began to translate texts and bring to light the magical nature of hieroglyphs.

English

English

Spain

Spain